An exhibit curated by a UC Merced professor reintroduces the seven-decade career of an American artist of Japanese descent who defied systemic racism and created a body of artwork true to her unique vision, even as the mainstream arts community kept her at arm’s length.

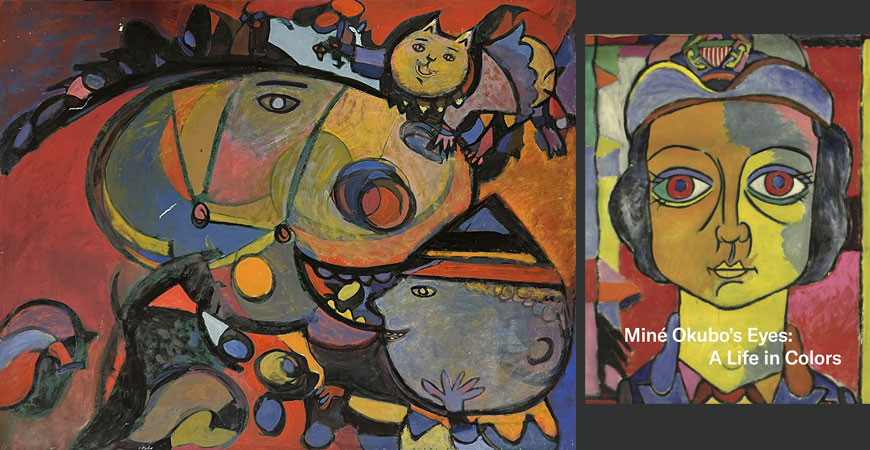

“Miné Okubo’s Eyes: A Life in Colors” opens April 26 at the Center for Social Justice & Civil Liberties, on the campus of Riverside Community College. The center is home to thousands of artworks, papers and memorabilia tied to Okubo, who was born in Riverside in 1912. The exhibit draws carefully from this treasure trove, building a chronological path in which Okubo’s artistic techniques, subjects and colors evolve through the decades.

Her art is represented in another exhibition, “Pictures of Belonging: Miki Hayakawa, Hisako Hibi and Miné Okubo,” a traveling presentation that, like the Riverside exhibit, is curated by ShiPu Wang , a UC Merced professor of art history and current Coats Family Chair in the Arts. It shows paintings and drawings by Okubo alongside the artworks of two other trailblazing Japanese American women.

The women lived under the oppressive shadow of the Exclusion Era, a period of significant discrimination against Americans of Asians descent and Asian immigrants. The era was marked by restrictive laws and policies that had a lingering effect on Asian American communities.

“Pictures of Belonging: Miki Hayakawa, Hisako Hibi and Miné Okubo,” currently on display at the Utah Museum of Fine Arts in Salt Lake City and recently featured in a New York Times story , follows the women’s creative output over eight decades. They share a brief and haunting period of history — all were torn from their homes and families, and Hibi and Okubo, an American citizen, were sent to incarceration camps following the Japanese attacks on Pearl Harbor in 1941. Sketches and paintings during their incarceration not only enabled them to retain their humanity but also served to document their wartime trauma.

“Pictures of Belonging” will go on display at the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington, D.C., in November.

The new retrospective in Riverside complements the traveling exhibition and offers a more expansive look at Okubo’s diverse body of work. Drawn from the center’s rich collection, many artworks will be seen by the public for the first time.

“What you find online is not necessarily her best work. She did not sell a lot. Museums did not collect her work when she was alive,” Wang said. “This show offers a whole different and more nuanced perspective on Okubo as an artist.”

Wang is scheduled to speak at an opening reception starting at 5:30 p.m. April 26.

Perhaps ironically, a monochromatic tempera painting of two intern camp guards by Okubo led to assignments from Fortune magazine in 1944. She moved to New York City’s Greenwich Village, where she remained for nearly six decades. In the 1950s, after years as a commercial illustrator, Okubo decided to focus on her own art. She painted and followed her muse wherever it led.

“She went through a period of simplifying her forms, simplifying colors, unlearning European artistic traditions to come up with her own visual language,” Wang said.

He arranged the Riverside exhibition in mostly chronological order to help the viewer understand Okubo’s artistic journey.

“If you don't have an organized view, it looks like, ‘Oh, she's just doing something today and then something else the other day.’ When you walk through this new retrospective, you will be able to see her development, exploration, experimentation and growth as an artist.”

The experimentation lasted through the 1990s. Flowery and colorful scenes. Fantastic creatures. Circuses. Abstract shapes and forms. All while battling the landlords of her rent-controlled apartment and getting little attention from the arts community. But friends said she never lost her zest for life or passion for her craft.

“Life and art are one and the same,” she wrote, “rooted in a concern for the humanities.”

Upon her death in 2001, Okubo’s estate followed her wishes and shipped nearly all her work and memorabilia to California museums. Most of it landed in her hometown, where she had attended what was then called Riverside Junior College (she went on to earn a master’s in fine arts at UC Berkeley).

Wang mined the center’s Okubo collection extensively for “Pictures of Belonging” and borrowed more than a dozen works, leaving the center’s walls with blank spaces. Curating “Miné Okubo’s Eyes” is a way for him to return the favor and engage in community work.

“When I jump into projects, I don’t think too much about what I’ll get out of it. But with this exhibition I realized how curating isn’t just about putting pretty pictures on a wall. It’s about working with community organizations — in this case one that advocates for social justice,” Wang said. “I want to leverage art to tell stories related to their mission.

“An exhibition is open to the public. They can come, explore and learn on their own. And that’s a form of community engagement in curating art exhibits.”